FROM IMPOSTER TO INNOVATOR: RECLAIMING YOUR CONFIDENCE IN CREATIVE WORK

Imposter syndrome is a condition in which a person views their achievements as insufficient. They feel that their intellect, talent, and competence are merely a façade they have managed to construct, with no genuine foundation behind them. They often hope that further education or an additional diploma will help rectify the situation.

A person sabotages their achievements. They are never satisfied with themselves and consider themselves insufficiently productive. This success does not integrate into their self-esteem even when they achieve something in their profession.

A few days ago, I discussed this with friends: she is a jeweller with diplomas from a prestigious art university and a jewellery school, while he is a renowned self-taught musician. She told me, "When people ask what I do, I say, ‘I make jewellery,’ but it’s very difficult for me to say, ‘I am a jeweller.’" Her husband, on the other hand, said, "I make music, which means I am a musician."

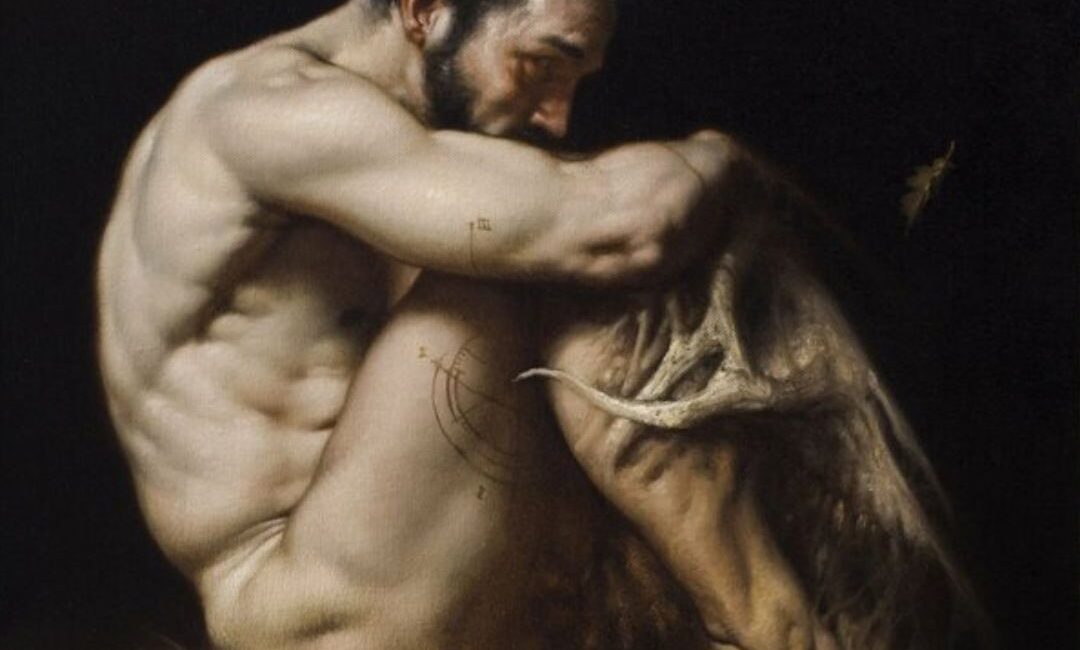

Imposter syndrome is precisely the divide between you and what you create. Within you, there is a perpetually dissatisfied part, always saying: "You can do better."

In my practice, I have encountered this syndrome in people of various professions, butit is particularly challenging for creative individuals. When a doctor says, "I am a doctor," it often garners respect. Society holds this profession in high regard. Doctors are granted an unearned level of trust. But when you say, "I am an artist" or "I am a photographer," people often react with scepticism. Creative individuals must constantly prove their right to a place under the sun. If you are not yet well-known, if magazines don’t write about you, it isn't easy to quantify your success.

From my experience working with artists, I know that those who grew up with non-artist parents had to prove their right to what they do from an early age. That’s why they develop an internal critic. They are split in two: they love art, but a part of them distrusts themselves and their creativity. They may even feel a bit envious of people with more "down-to-earth" professions.

For an artist, seeking validation from the external world is dangerous. From the history of art, we know examples and biographies where the works created by artists were ahead of their time and received no recognition from most of their contemporaries. This was the case, for instance, with Van Gogh. The same thing happened in science. Giordano Bruno was burned at the stake because he insisted that the universe is infinite.

How did they manage not to doubt the purpose of their lives, and where did they find the strength to remain true to their ideas, even when almost the entire world devalued their work?

A creative person needs to find support within themselves. But not in a narcissistic complex, such as “Everything is crap, and I’m an artist,” but in their own internal values.

Ask yourself: Why do I love art? What would my life be without it? What do I feel when I visit museums, exhibitions, concerts? When I read poetry or a good novel? Why, during the war, did artists hold concerts in hospitals and lift the spirits of wounded soldiers? Why do people with serious brain injuries, with the loss of certain functions, regain lost abilities when they engage in creative activities? By answering these questions, you will discover your fundamental values, which you can use to counter doubt. This way, you will confront your inner critic, that devaluing part of you that undermines your foundation. You will defeat the demons of doubt, stop wasting your priceless energy on them, and instead direct it towards realizing your creative ideas. You will stop overthinking and start doing more.

Below are some practical recommendations that, despite their simplicity, work flawlessly:

Imposter syndrome is self-doubt; it is the habit of being dissatisfied with your results. You don't integrate positive experiences into your self-concept because you explain them as mere luck. However, you judge yourself harshly for any negative experience. It’s as if you have a special filter that works against you and reinforces your negative perceptions about yourself.

Therefore, it is important to learn to notice positive experiences to build new neural connections. Keep a journal where you write everything you have achieved: the problems you solved throughout the day, everything you've done. Train yourself tofocus on what you can do and what you succeed at. If you suffer from imposter syndrome, you probably rarely praise yourself, but you criticize and devalue yourself at any opportunity.

You need to stop comparing yourself to others. A creative person who does not compare themselves as an individual or as an artist to others does not devalue themselves. Their sense of self-worth remains intact. You can compare individual skills, and that will help you improve your craft, but never compare your whole self. This is the key difference between those who experience the syndrome and those who never have.

The next piece of advice is to learn to set clear, realistic goals. Break large goals into many small steps, and develop the habit of having a to-do list every day. Structure your day and then follow your plan with discipline. You may experience emotions during the creative process, but when it comes to organizing it, be as emotionless as a machine. Become a good manager of yourself.

Our consciousness is designed to evaluate any information based on its influence on our goals. This is why we react so painfully to our failures. Information or experiences that do not align with our desires create mental entropy. This is chaos of thoughts and feelings that distracts our attention from the process and throws us off our path.

To reduce the likelihood of entropy, it is important to stop thinking in terms of external rewards. You need to learn to find rewards within yourself, developing the ability to rejoice regardless of external circumstances.

The opposite of mental entropy is the state of flow. This is precisely what we can use to counteract imposter syndrome in order to remain strong and move forward without wasting our energy. These states have been studied by many psychologists, and there is a wonderful book by the Italian author Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. This book is listed among the 100 best books for businesspeople and leaders.

Every person experiences a state of flow. It arises when you are engaged in something so interesting that you become one with the activity. You are like a child engrossed in play. You are focused on the task, and therefore unnecessary thoughts—mental entropy—do not interfere with the process and do not disrupt it.

You are absorbed in what you are doing, you don’t feel time passing, and you have no doubts about your competence; there is only joy from the activity itself.

A person enters a flow state when clear goals are set before them, and they feel that they are succeeding, that everything is going as it should. They receive feedback from the process that motivates them to continue.

How can an artist receive this feedback when they do not have a clearly set goal in advance?

If the artist creates their work in a flight of fantasy, intuitively, without having a clear idea of the final result, they must have an internal criterion for what is good and what is bad. So that after each brushstroke, they can tell themselves: "Yes, this is it" or "No, it needs to be different." This is how they provide themselves with feedback and remain in the flow state.

Remember, the more focused you are, the less entropy arises: you are not distracted by doubts and you don’t devalue yourself.

Let’s step-by-step look at how to create conditions for a flow state:

- Set a clear goal for yourself and focus on its implementation.

- The goal should match your skill level.

- You should receive immediate feedback during the process, feeling that what you're doing is correct.

The task you set for yourself must be neither too difficult nor too easy. A person easily loses interest in something that is too hard for them, but they also quickly get bored when doing something too simple. Once you’ve perfected yourself at a certain stage or technique, slightly increase the level of difficulty. But make sure the new tasks you set for yourself are still clear and manageable.

For the flow state, it is important that your activity is not done for a future reward, but for the activity itself. The artist creates not to finish the painting, but because they love to paint. The teacher teaches because they enjoy sharing knowledge.

In a flow state, we may lose our sense of self. We stop thinking about ourselves. This is very good for the process because unnecessary self-focus is very draining in terms of mental energy. For example, if I arrive at a party worried about what impression I’m making on others, whether I look okay, or if something is wrong with me, these thoughts will distract part of my attention from the outside world. I’ll likely miss a lot of what’s happening around me, feel tense, and not meet the right people.

In the flow state, there is no self-analysis. You derive joy from your activity, feeling that you are heading in the right direction. You are performing a task that matches your abilities, so your sense of self is not threatened.

Although you forget about yourself, your self-concept expands in the flow state because you are working and improving your skills. When you complete the task, your sense of self will be enriched with new abilities.

By now, it should be clear that the flow state is the opposite of the complex of thoughts and feelings typical of imposter syndrome.

When you doubt yourself or your work, you are in an egocentric position, even though it’s negative.

Self-obsession is a significant obstacle to the flow state. When a person fears making a bad impression or doing something wrong, they can’t experience joy from their activity. The end result becomes more important than the process itself. The process holds no value for them, and they cannot fully immerse themselves in it.

Psychologist Richard Logan analyzed individuals who had endured extreme experiences, such as being in concentration camps or other life-threatening situations. He discovered that those who managed to survive these horrific conditions shared one common trait: non-egocentric individualism.

These individuals had a purpose that they placed above their personal interests. Even in hopeless situations, they continued to move toward their goal. This internal motivation helped them persevere. Because they were not self-absorbed, they retained more mental energy, which they used to assess their external circumstances. As a result, they were better able to spot new opportunities.

A person with a narcissistic character is likely to falter in difficult situations because they are primarily focused on protecting their sense of self. Their attention is directed inward, attempting to restore order within their mind. This leaves them with little energy to find creative solutions.

The individuals Richard Logan studied had another empowering belief: they believed their fate was in their own hands, and they had enough resources to cope with whatever challenges came their way.

Do you see the difference? These people were confident but not egocentric. They did not aim to dominate the world around them. Instead, their energy was focused on existing harmoniously within it.

This is why it's so important to learn to do everything possible within the circumstances you're in. For this, you need to trust yourself, trust the world around you, and trust your place in it.